Call for action – what can mental health practitioners do to understand and manage the risk of suicide behaviour?

By Gunjan Y Trivedi, PhD

(Co-founder, Society for Energy & Emotions, Wellness Space, [email protected])

Note: This article was published in the magazine “Just let go” – by Clover Leave Academy (2024)

Introduction:

India, 18% of the world population, accounts for 28% of the global suicide numbers. Evidence indicates that 90% of the individuals who attempt suicide have a history of mental health issues. Unfortunately, with >250 million young adolescents, suicide is the primary cause of death among young Indians (Age 15-39). A growing economy will bring more young Indians to work, increasing the risk of stress. With the limited availability of resources for mental health, India is facing a potential public health and productivity disaster. Despite existing research in India on suicide behaviour (which includes a history of suicidal thoughts a history of suicidal plans, or attempts), there is a glaring gap in understanding this complex issue[1].

What is suicide behaviour?

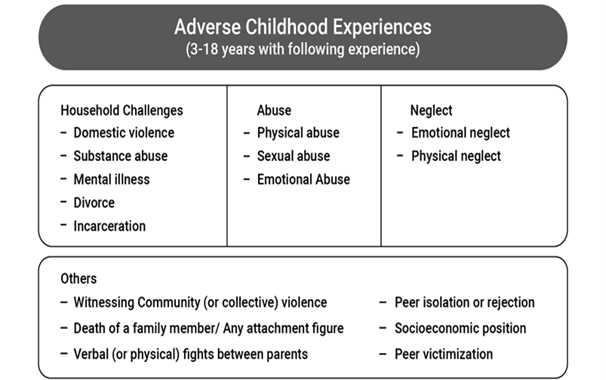

Suicide behaviour is a complex problem with many contributors. Research has established a strong link between mental health issues, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs or childhood trauma) and adult suicide behaviour[2]. Individuals with a history of childhood abuse, neglect or other types of traumas (Figure 1) are at an increased risk, potentially making them more vulnerable to stressful events in their lives. Moreover, internalising issues (high levels of depression, anxiety) and specific behavioural issues (such as a history of self-harm, history of making irrational decisions, and violent behaviour) also increase the risk. The key message for everyone, including parents and mental health workers, is to understand the root causes or risk factors and work to minimise the risk.

Figure 1 – Adver Childhood Experiences (ACEs) or Childhood Trauma[3]

Insights from our work:

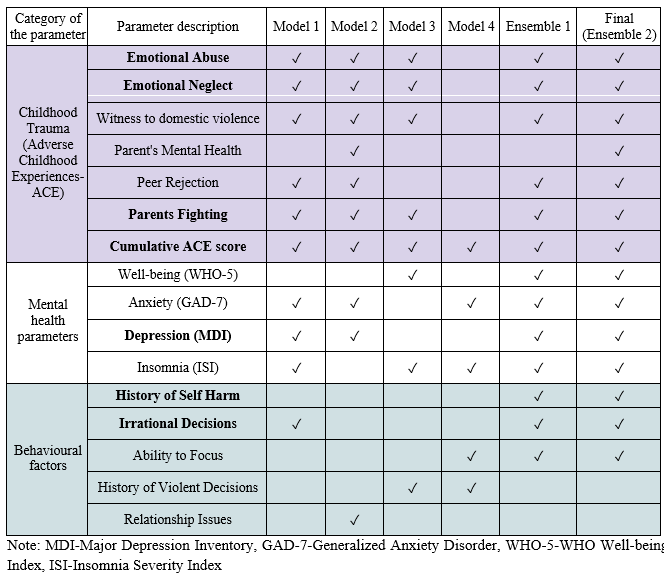

We have collaborated with various experts (preventive medicine, neuroscience, psychology, psychiatry and psychotherapy) to understand the risk factors of suicide behaviour, which has resulted in initial findings. Several members of our team (Riri G Trivedi, Neha Pandya, Dr Hemalatha Ramani) have been working on learning about suicide behaviour[4]. The findings are summarised in the table below (based on published data using a machine learning algorithm to understand the risk factors of suicide behaviour)[5].

Table 1 – Machine learning algorithm and key features

The table provides a list of parameters linked to increased risk of suicide behaviour across different algorithms explored. The findings confirmed that cumulative childhood trauma (ACE score), specific childhood trauma experiences (e.g. emotional abuse and neglect), depression, history of self-harm, history of making irrational decisions, etc, are key risk factors as per the findings covering >600 individuals’ data. The findings provide a uniquely Indian perspective for mental health practitioners, parents and caregivers of young children.

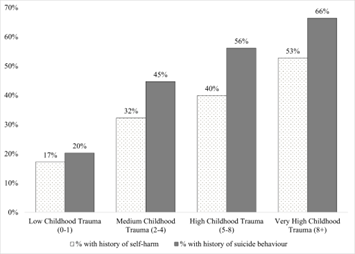

Example – Prevalence of self-harm and suicide behaviour & childhood trauma exposure levels

Two specific examples are highlighted to provide the association between the exposure levels of childhood trauma and the prevalence of self-harm history and suicide behaviour history in each trauma category (low, medium, high and very high), as shown in Figure 2. Adults who have been exposed to childhood trauma are more likely to exhibit such behaviours.  Figure 2 – Childhood trauma exposure (low, medium, high and very high) and prevalence of (a) self-harm and (b) suicide behaviour history

Figure 2 – Childhood trauma exposure (low, medium, high and very high) and prevalence of (a) self-harm and (b) suicide behaviour history

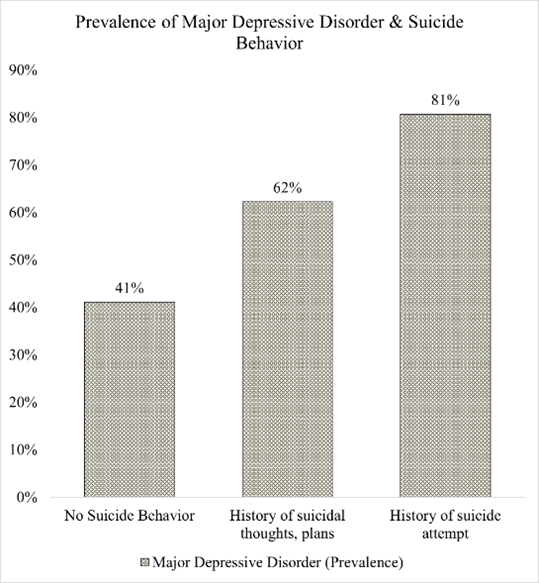

Figure 3 – Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder and Suicide Behavior

Figure 3 shows the presence of high depression levels (also known as Major Depressive Disorder-MDD) in individuals without a history of suicidal behaviour and with a history of suicidal behaviour (thoughts, attempts). The prevalence of MDD increases as we move from no suicide behaviour to suicidal thoughts and eventually the suicide attempt history group.

Such insights are critical, and they provide context and actionable areas for mental health practitioners. The evidence-based approach can help us understand the phenomena of the “inner child” through precise assessment of ACEs via personal interviews.

Conclusion:

The findings confirm the associations between several childhood trauma components, internalisation issues, behaviour issues and adult suicide behaviour. Most of these risk factors are preventable, so mental health practitioners must understand, identify, and address them

What can mental health practitioners do?

- Please assess childhood trauma’s history (presence, frequency), primarily via personal interview. If the trauma exposure is high, screen for additional risk factors.

- Please measure depression levels and history of self-harm, irrational decision making or suicidal thoughts.

- If there is significant childhood trauma exposure, a history of self-harm, and high levels of depression, we recommend a thorough suicide risk assessment (ASK-Suicide-Screening Questions).

- Please seek an alternative opinion based on ASQ findings (e.g. consult a psychiatrist) before therapeutic intervention

- Addressing the drivers of depression and behavioural factors is critical. Identify the presence of Complex Trauma (CPTSD or Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder)[6]. Individuals with exposure to emotional abuse and neglect are at a higher risk, though a comprehensive trauma assessment is necessary.

- Increase awareness about the risk factors of suicide and integrate them into parental behaviour and education.

References:

[1] Suicide behaviour is different from self-harm (NSSI: Non-Suicidal Self Injury), where the intention is not to take life.

[2] Trivedi, G. Y., Pillai, N., & Trivedi, R. G. (2021). Adverse Childhood Experiences & Mental Health–the urgent need for public health intervention in India. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene, 62(3), E728.

[3] Trivedi, G. Y., Ramani, H., Trivedi, R. G., Kumar, A., & Kathirvel, S. (2023). A pilot study to understand the presence of ACE in adults with post-traumatic stress disorders at a well-being centre in India. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(4), 100355.

[4] Source: K Rao, A., Y Trivedi, G., Bajpai, A., Singh Chouhan, G., G Trivedi, R., Kumar, A., … & Ramani, H. (2023, July). Predicting Adverse Childhood Experiences via Machine Learning Ensembles. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (pp. 773-779).

[5] Rao, A. K., Trivedi, G. Y., Trivedi, R. G., Bajpai, A., Chauhan, G. S., Menon, V. K., … & Dutt, V. (2023, October). Predicting suicidal behavior among Indian adults using childhood trauma, mental health questionnaires and machine learning cascade ensembles. In International Conference on Frontiers in Computing and Systems (pp. 247-257). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

[6] Trivedi, G. Y., Ramani, H., Trivedi, R. G., Kumar, A., & Kathirvel, S. (2023). A pilot study to understand the presence of ACE in adults with post-traumatic stress disorders at a well-being centre in India. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(4), 100355.

Leave A Comment